Daily Newsletter 4/100:The Breaking Point

Why some pitches succeed when you think they shouldn't.

Why some pitches Succeed when they “Shouldn’t”

I have said it once and i’ll say it again: Everyone in baseball is looking for an edge, and when it comes to pitch design, understanding Vertical Approach Angle (VAA) and Horizontal Approach Angle (HAA) is one of those edges that separates good pitches from elite ones. VAA is all about how steep or flat a pitch enters the zone. The flatter the angle (closer to -4.0°), the better it plays at the top of the zone, which is similar to high-spin fastballs with carry that generate so many whiffs up there. On the other hand, a steeper VAA (like -6.0° or more) is what makes a sinker or low fastball tough to lift, generating ground balls and weak contact.

HAA, meanwhile, tells us how a pitch approaches the plate from side to side. A high HAA means the pitch comes in at a tough angle, which is why sweepers and running fastballs work so well against certain hitters.

Example: Bryan Woo

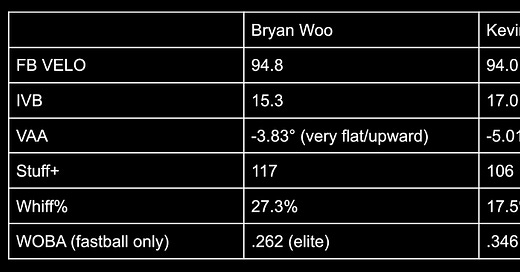

Brian is a really interesting example. if you strictly look at the induced movement on his fastball you wouldn't think it's anything crazy. however, if you look on MLB pitch profiler you will realize the Stuff+ on his fastball is a 117. This is an absolute weapon of a fastball. However, it has a very average movement profile, averaging 15vb and 10 hb. This movement type is what people call “deadzone” the worst possible place to be as a pitcher: not enough vertical movement to be a good rise ball, but also too much to be a good sinker. However, it is potentially the best sub 95mph fastball (94.8 avg in 2024) in the entire game, how is this the case?

Simply, the amount of vertical movement created is completely mismatched from the release point. Bryan is 6’2 and releases the ball at about a 5.8 feet off of the ground. Let's compare this to another pitcher with an above average fastball. Kevin Gausman is also 6’2 and also averages 94 mph on his fastball from a 6.2 release height.

Both of these fastballs are good, but Woo’s is elite. His is significantly more effective than Gausman’s despite having 10% less vertical movement. His fastball is carried by the angle at which it is thrown. After Woo pitched against the yankees, it garnered enough attention that opposing manager Aaron Boone chimed in saying “that heater is real” after woo threw 6 scoreless against them.

These can be really difficult to pick up with the naked eye, but you can see them easier with video.

Camera angles can be deceiving, so this is just a piece of the puzzle. Looking at where the release point is in relation to their body can help.

HAA: a more general rule of thumb

HAA is significantly more manipulatable than VAA, with pitchers being able to change it multiple feet at a time simply by adjusting where they stand on the rubber. Pitchers will adjust the side of the rubber they throw on in order to create different advantages against different hitters.

Paul Skenes is a perfect example of this, he slides as far to the third base side of the rubber as he can against left handed hitters, to create a more out to in feeling for the hitter against his pitches. While against right handed hitters he slides to the first base side, getting more neutral and allowing his sinker to play better against them.

VAA is very cut and dry, but HAA is more of a spectrum of benefits at the moment. Some things work multiple ways, and since you often manipulate HAA by your place on the rubber, it is important to weigh all the possible drawbacks it could have to every pitch in your arsenal.

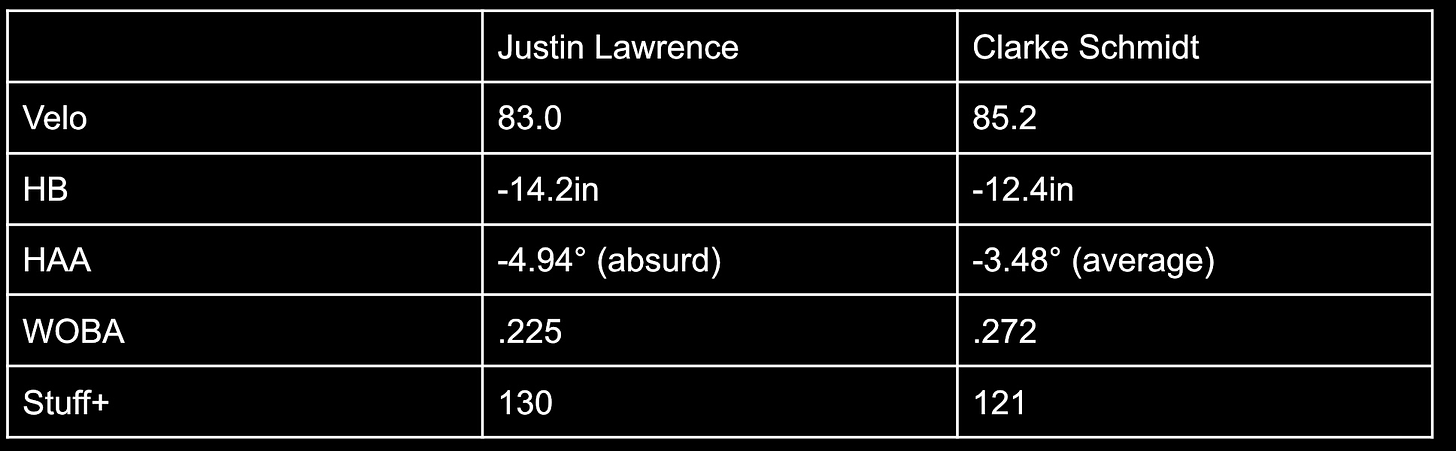

Here is a comparison on two sweepers, and how they both create their value.

Lawrence sees significantly better results from his sweeper than Schmidt does, despite throwing it 2 mph slower and it only moving 1.8 inches more. Below is some basic data on HAA.

The average Horizontal Approach Angle (HAA) for a right-handed MLB pitcher varies slightly by pitch type, but generally falls in the range of -1.5° to -3.0°.

Here’s a breakdown by pitch type:

Four-seam fastballs: ~-1.5° to -2.5° (minimal horizontal deviation)

Two-seam fastballs/sinkers: ~-2.5° to -3.5° (more arm-side run creates a steeper negative HAA)

Changeups: ~-2.5° to -4.0° (heavy arm-side fade increases HAA)

Sliders (gyro-style): ~-1.0° to -2.0° (minimal horizontal break, mainly vertical movement)

Sweepers: ~-3.5° to -5.0° (high horizontal break increases HAA)

Curveballs: ~-1.0° to -3.0° (depends on tilt and release slot)

In general, most righties sit between -2.0° and -3.0° across their arsenal. Pitchers with higher arm slots tend to have smaller (closer to zero) HAAs, while lower slot guys or sweep-heavy pitchers generate larger HAAs.

Hitters are finding some ways to combat same-handed HAA by shifting their batting stance to more open offset the steep HAA’s, but overall the approach angle of pitches is incredibly difficult to defend against. Pitch movement has trade offs of being harder to get certain pitches in the zone of they move a lot, or being easier to pick up because. HAA/VAA have staying power, and are helping us evaluate and create plans for pitchers at the highest levels.

John